Scripture and Tradition

Scripture and Tradition

Catholic Outlook

Catholic Outlook

Catholic Outlook

Scripture and Tradition

Scripture and Tradition

__________ Recent Additions __________

Catholic Outlook

Catholic Outlook

Tampering with the Word of God

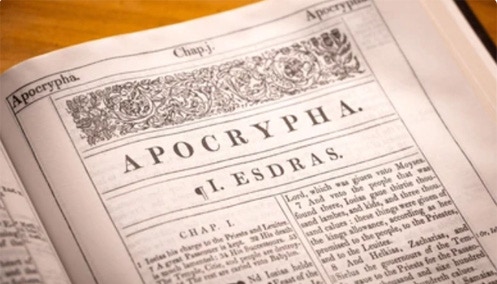

Did the Catholic Church add the “Apocrypha”

to the Bible at the Council of Trent?

Gary Hoge

Catholic and Protestant Bibles have the same New Testament, but Catholic Bibles have seven Old Testament books that Protestant Bibles don’t have. Catholics call these books the “deuterocanonical” books. Protestants call them the “Apocrypha.”

Many Protestants claim that the Catholic Church stuck these extraneous books into the Bible in response to the Protestant Reformation, apparently in an attempt to lend credibility to its unbiblical teachings. Protestant author Josh McDowell writes:

It cannot be overemphasized that the Roman Catholic Church itself did not officially declare these books Holy Scripture until 1545-1563 at the Council of Trent. The acceptance of certain books in the apocrypha as canonical by the Roman Catholic Church was to a great extent a reaction to the Protestant Reformation. By canonizing these books, they legitimized their reference to them in doctrinal matters.1

In other words, when the Reformers said, “The Bible doesn’t teach things like prayer for the dead,” the bishops at the Council of Trent tacked the book of 2 Maccabees onto the Old Testament and said, “Now it does!”

But is that true? Let’s look at the “Decree Concerning the Canonical Scriptures,” issued by the Council of Trent, the 19th ecumenical council, on April 9, 1546:

“The sacred and holy, ecumenical, and general Synod of Trent, – lawfully assembled in the Holy Ghost, … yada, yada, yada … following the examples of the orthodox Fathers, receives and venerates with an equal affection of piety, and reverence, all the books both of the Old and of the New Testament – seeing that one God is the author of both … yada, yada, yada … And it has thought it meet that a list of the sacred books be inserted in this decree, lest a doubt may arise in any one’s mind, which are the books that are received by this Synod. They are as set down here below: of the Old Testament: the five books of Moses, to wit, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Joshua, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings [i.e., 1 Samuel, 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, 2 Kings], two of Chronicles, the first book of Ezra, and the second which is entitled Nehemiah; Tobit, Judith, Esther, Job, the Davidical Psalter, consisting of a hundred and fifty psalms; the Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Canticle of Canticles, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Isaiah, Jeremiah, with Baruch; Ezekiel, Daniel; the twelve minor prophets, to wit, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; two books of the Maccabees, the first and the second. Of the New Testament: … ; [they go on to list the 27 New Testament books we all accept today].”2

As you can see, right there in plain Latin, Trent did indeed include the “Apocrypha” in its list of Scripture. But did the Council add them, as Josh McDowell claims, or were they there all along? To find out, let’s jump back 104 years, to the 17th ecumenical council, the Council of Florence.

This council took place 75 years before the Protestant Reformation began; 41 years before Martin Luther was even born. On February 5, 1442, the Council of Florence issued the following:

“[T]his sacred ecumenical council of Florence … professes that one and the same God is the author of the old and the new Testament – that is, the law and the prophets, and the gospel – since the saints of both testaments spoke under the inspiration of the same Spirit. It accepts and venerates their books, whose titles are as follows. Five books of Moses, namely Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Joshua, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings [i.e., 1 Samuel, 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, 2 Kings], two of Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Tobit, Judith, Esther, Job, Psalms of David, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Baruch, Ezechiel, Daniel; the twelve minor prophets, namely Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; two books of the Maccabees … ; [they go on to list the 27 New Testament books we all accept today].”3

As you can see, the Council of Florence listed exactly the same books that would be listed by the Council of Trent 104 years later. And this list was approved by Pope Eugene IV.

But didn’t Josh McDowell say, “The acceptance of certain books in the apocrypha as canonical by the Roman Catholic Church was to a great extent a reaction to the Protestant Reformation”?4 If so, the Catholic Church was apparently able to react to the Protestant Reformation 75 years before it even started, which is a pretty impressive feat! Either that, or McDowell was wrong.

But doesn’t this just move the problem back a century? I mean, adding books to the Bible in 1442 is just as bad as adding them in 1546. So, wouldn’t it be accurate to rephrase McDowell’s objection and say, “It cannot be overemphasized that the Roman Catholic Church itself did not officially declare these books Holy Scripture until 1442 at the Council of Florence”? No, actually that would be wrong, too.

Let’s go a thousand years farther back in time to the north-African town of Hippo Regius, in modern-day Algieria. In 393 AD the regional Synod of Hippo issued a list of Scripture. It may look familiar:

“Besides the canonical Scriptures, nothing shall be read in the church under the title of divine writings. The canonical books are: – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, the four books of Kings [i.e., 1 Samuel, 2 Samuel, 1 Kings, 2 Kings], the two books of Chronicles, Job, the Psalms of David, the five books of Solomon [i.e., Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Song of Songs, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus], the twelve books of the Prophets [i.e., Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi], Isaiah, Jeremiah [including Baruch], Daniel, Ezekiel, Tobit, Judith, Esther, two books of Esdras [i.e., Ezra, Nehemiah], two books of the Maccabees. The books of the New Testament are: – the four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, thirteen Epistles of S. Paul, one Epistle of S. Paul to the Hebrews, two Epistles of S. Peter, three Epistles of S. John, the Epistle of S. James, the Epistle of S. Jude, the Revelation of S. John. Concerning the confirmation of this canon, the transmarine Church [i.e., the Roman church] shall be consulted.”5

Just like the future councils of Florence and Trent, the Synod of Hippo also included the deuterocanonical books in its canon. In case you’re keeping track, this synod published its canon of Scripture 1,086 years before Martin Luther was born, 1,120 years before he nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, and 1,149 years before the Council of Trent.

Clearly, the Catholic Church did not add the “Apocrypha” to the Bible in response to the Protestant Reformation. The only change to the Bible that resulted from the Reformation was on the Protestant side, where these seven Old Testament books were downgraded and shunted off into an appendix, and eventually removed altogether.6

In case you’re wondering what the Church’s canon of Scripture was before the Synod of Hippo, it didn’t have one. The Synod of Hippo, though it was a regional council, and not binding on the whole church, was the first Church council to produce an official list of canonical books. And that is true of the New Testament books, too, as this Protestant source confirms:

It was not until the year A.D. 393 that a church council first listed the 27 New Testament books now universally recognized. There was thus a period of about 350 years during which the New Testament Canon was in process of being formed.7

In the years before the Synod of Hippo, the canon of Scripture varied from place to place. Certain books were universally accepted (e.g., Genesis, Isaiah, Ephesians, the Gospel of John), but others were disputed (e.g., Esther, Tobit, Hebrews, 2 Peter). For example, as late as A.D. 324, the Church historian Eusebius of Caesarea wrote,

One epistle of Peter, that called the first, is acknowledged as genuine. And this the ancient elders used freely in their own writings as an undisputed work. But we have learned that his extant second Epistle does not belong to the canon … Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the second and third of John, whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name. (Eusebius, History of the Church, 3:3:1, 3:25:3, 324 A.D.).

The seven deuterocanonical books were among those that were sometimes disputed, but they were accepted by most Christians, as Protestant scholar J.N.D. Kelley confirms:

[The Old Testament] always included, though with varying degrees of recognition, the so-called Apocrypha or deutero-canonical books. … In the first two centuries . . . the Church seems to have accepted all, or most of, these additional books as inspired and to have treated them without question as Scripture. Quotations from Wisdom, for example, occur in 1 Clement and Barnabas . . . Polycarp cites Tobit, and the Didache [cites] Ecclesiasticus. Irenaeus refers to Wisdom, the History of Susannah, Bel and the Dragon, and Baruch. The use made of the Apocrypha by Tertullian, Hippolytus, Cyprian and Clement of Alexandria is too frequent for detailed references to be necessary.8

Likewise, the Protestant International Bible Commentary says,

Even if one holds that Jesus put His imprimatur upon only the 39 books of the Hebrew OT, as is implied above, he must admit that this fact escaped the notice of many of the early followers of Jesus, or that they rejected it, for they accepted as equally authoritative those extra books in the wider canon of the LXX9 . . . Polycarp [one of John’s disciples], Barnabas, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Cyprian, Origen – Greek and Latin Fathers alike – quote both classes of books, those of the Hebrew canon and the Apocrypha, without distinction. Augustine (A.D. 354-430) in his City of God (18.42-43) argued for equal and identical divine inspiration for both the Jewish canon and the Christian canon.10

It seems strange to me that the Reformers would adopt the “Jewish canon” and reject the “Christian canon,” but they did. Stranger still is the fact that centuries later their spiritual descendants think the “Jewish canon” is the “Christian canon,” and that the extra books in Catholic Bibles were added to the Bible by Catholics, when in reality those books were removed from the Bible by Protestants. But hopefully, now that you know the truth, you’ll agree with Marvin Tate, Old Testament professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, who wrote,

“It seems clear that the Protestant position must be judged a failure on historical grounds, insofar as it sought to return to the canon of Jesus and the Apostles. The Apocrypha belongs to this historical heritage of the Church.”11

__________

1 Josh McDowell and Don Stewart, Answers to Tough Questions Skeptics Ask About the Christian Faith, (San Bernardino, CA: Here’s Life Publishers, Inc., 1980), 37.

2 Council of Trent, Fourth Session, Decree Concerning the Canonical Scriptures, April 8, 1546.

3 Council of Florence, Eleventh Session, February 4, 1442.

4 McDowell et al., Answers, 37.

5 Synod of Hippo, Canon 29, A.D. 393.

6 In his German translation of the Bible, Martin Luther also placed four of the New Testament deuterocanonical books (Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation) in an appendix. He did not consider them to be inspired Scripture, but thought they otherwise contained “many good sayings” (Luther’s Works, 35, 397). Fortunately, the other Reformers did not follow Luther’s lead, which is why these four books remain in Protestant Bibles today.

7 David F. Payne, “The Text and Canon of the New Testament,” International Bible Commentary, ed. F.F. Bruce, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1986), 1005.

8 J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrine, (New York: Harper & Row, 1960), 53-4.

9 The LXX, or Septuagint, was the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament. This is the version the ancient Christians, including the authors of the New Testament, mainly used. In fact, most of the Old Testament quotations found in the New Testament come from the LXX, not from the Hebrew version.

10 Gerald F. Hawthorne, “Canon and Apocrypha of the Old Testament,” International Bible Commentary, ed. F.F. Bruce, (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1986), 37, 35.

11 Marvin Tate, “Old Testament Apocalyptica and the Old Testament Canon,” in Review and Expositor 65, 1968, 353.

Copyright © 2024 Catholicoutlook.me

MENU